The locked door – The life and death of Dr. Srinivas Ramchandra Siras | Rishi Majumder

13 June, 2016

Dr. Shrinivas Ramchandra Siras didn’t deserve to die. More to the point, he didn’t deserve to live like he did.

If you watch Aligarh, Hansal Mehta’s film on Siras’ life, read about Siras or talk to those who knew him one image is likely to stay with you after. That of a locked door.

Siras’ door was locked, on February 8, 2010, when local cable TV journalists secretly filmed him having sex with another man, Abdul, before barging into his house in Aligarh to confront him. They kept the camera rolling. The footage apparently shows Siras pleading with them to stop filming.

Why? Homosexuality wasn’t a crime back then. Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which has been reinstated by the Supreme Court now, had been read down by the High Court at the time for being unconstitutional. Why then did Siras, instead of calling the police and reporting the miscreants, have to grovel before two intruders in his own home?

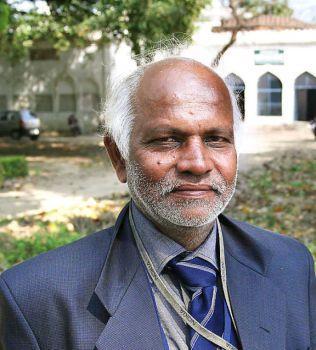

Siras was a poet and teacher of Marathi and Chairman of the Department of Modern Indian Languages at the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU). When the university authorities learnt of the footage, they decided to suspend Siras instead of lodging a complaint against those who had spied and trespassed on university property. Some have suggested that the Vice Chancellor, Dr. P. K. Abdul Aziz, saw the incident as an opportunity to divert attention from the corruption charges he was facing, as well as a way to gain support from orthodox influencers at the institution at a vulnerable time.

The university’s action was backed by a campaign against Siras begun by a group of students as well as by statements from faculty members and university officials such as ones which claimed he had acted against AMU’s ‘history of culture and tradition’ and that ‘such acts give rise to AIDS’.

The statements were in clear denial of the most basic human rights. The last one was especially ridiculous because it was made by an associate professor of law at the university.

In addition, the element of class was infused into pre-existing prejudice to magnify its effect. Ashu Rizvi, who ran a cable news outfit when he filmed Siras that night – he is now in the real estate business – has said to the BBC that he saw what he did as a “legitimate story of uncovering the exploitation of a rickshaw puller (Abdul, who was Siras’ sexual partner when he was filmed) by a university professor”.

Abdul himself has denied any exploitation on Siras’ part. But no matter. So long as a witness is poor and voiceless, his or her stereotype serves as a tool for breeding bigotry.

Siras fought the university in court. He won. Less than a week after the judgment he died, mysteriously, on 7 April 2010, a day before the letter officially revoking his suspension arrived at his office.

Until journalists and commentators, such as Indian Express reporter Deepu Sebastian Edmond, pointed out the ridiculousness of their assumptions, police officials claimed Siras’ death was a consequence of suicide.

How did they arrive at this conclusion? The door to his room was locked from within, they said.

An array of evidence, including traces of poison found during Siras’ autopsy, leaves many unanswered questions surrounding the professor’s death.

~

But that’s really beside the point isn’t it? The point is Siras died and the question of whether he committed suicide or not is a digression from the larger questions staring us in the face.

One such larger question is, once again: Was Siras really living in the first place?

Another question is Section 377. That heinous section of the Indian Penal Code, now back in action, that brands an individual a criminal for his or her harmless sexual preferences.

The section says: ’Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal shall be punished with imprisonment for life, or with imprisonment of either description for term which may extend to ten years, and shall also be liable to fine.’

When we come across a film on an incident of discrimination and crime that occurred years ago it usually seems to say to us: ‘Look, we were so badly off before. Remember that and never go there again.’ Aligarh, which brought the Siras case back to the forefront of public discourse this year, isn’t such a film. Aligarh tells us: ‘Look, the shit hit the fan back then. Now you’re swimming in it.’

The truth is, even reading down this provision criminalizing homosexuality didn’t prevent Siras from being harassed, humiliated and risk losing his source of livelihood. Siras had been teaching at AMU for 22 years. He was supposed to retire in September, four months after he died. The AMU campus, like any major university campus, is like a world unto itself. The alienation of a man who has been cast out of and scarred by the place he has grown to call home is indescribable, but Aligarh captures some of it.

And yet, for Siras, the High Court’s reading down of Section 377 did seem to stand for something more than the bittersweet spoils of a victory hard fought and won against his own. It gave him a second shot at life. ‘I want to work for the gay community,’ Siras had said to Edmond after the court ruled in his favour. Edmond quotes him in The Indian Express saying: “I want to go to America. I want to teach them Marathi… America is the only place where I will be free to be gay.”

By bringing Section 377 back into force, the Supreme Court has held it isn’t in contravention of the Indian Constitution. Not Article 21 which says, ‘No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except by procedure established by law.’ Not Article 19(1)(a) which says, ‘All citizens shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression.’ The Supreme Court judgment could be questioned on many points of law and it has been questioned by legal commentators and activists. But let’s leave the law aside for a moment and respond emotively to the issue at hand.

Indians belonging to quarters inclined to discussing such matters often wonder whether LGBT rights in the country comprise a substantive free speech issue. Whether, in the roster of assaults on free speech in the country, it should be placed high up on the priority list.

To answer, one has to merely think of Section 377, Articles 19 and 21 and the image of a man pleading with intruders not to film him in his own house.

Free speech is implied as much as stated. It is an attitude as much as an action.

Think of the ‘journalists’ who entered Siras’ home that night, setting off this sequence of events. Also, of journalists such as Edmond, who followed Siras’ story closely and brought forth truth and perspective.

Finally, spare a thought for that locked door. There are many more behind it.

Submit a Comment